Safed (Tzfat) – Full Visitors Guide – The city of Kabbalah

Safed (Tzfat) is one of the four holy cities. Moreover, it is the highest city in Israel and is located in the northern region.

Table of Contents

- 1 Map

- 2 What does Safed mean?

- 3 What will this guide cover?

- 4 Weather

- 5 When Not To Visit Safed?

- 6 Tours

- 7 Saraya

- 8 Davidka Square

- 9 The City Police Station

- 10 Safed Synagogues

- 11 Messiah’s Alley

- 12 Safed Yeshiva

- 13 Safed Candles

- 14 Ari Ashkenazi Synagogue

- 15 Abuhav Synagogue

- 16 Blue Color in Safed (Tzfat)

- 17 Lahuhe original – Yemenite food bar

- 18 Citadel Park

- 19 Klezmer Festival

- 20 Artists’ Quarter

- 21 Underground Tunnels

- 22 Safed Cheese

- 23 Where To Stay

- 24 History

- 25 Common Questions

- 26 Summary

Map

Interactive map of the area:

And here is a map for tourists:

Note: you can click on the map to enlarge it.

Directions

If you reach Safed by public transport, you will probably take a bus. You can also take the train to Carmiel and take a bus from there. Here is an already preset link to Moovit, where you can enter your starting point and get updated directions.

Parking

In case you are driving, you will need to find parking. On two occasions, we parked near the Saraya. There is parking in front and behind it (at Aliya Bet street). There are parking places near Citadel Park (on Hativat Yiftach road). And as the sign suggests, there is also parking at Keren HaYesod street, below the Artists’ quarter. There are others, but remember that most are paid parking (blue and white curb). You can pay at a parking meter or via an app (see useful apps). I do not remember the exact price, but it was around 2.5 NIS per hour. In any case, I would suggest not entering the Old City since it is very dense and the chances of finding a place are slim.

What does Safed mean?

There is no consensus about what is the origin of the name Safed. But the name Safed (Tzfat) resembles the Hebrew word for observing. Moreover, since Safed is the highest city in Israel, it is an excellent observation point. And according to this questionnaire by the Ministry of Education, Tzfat received its name since you can see both the Middeternian Sea and the Sea Of Galilee.

What will this guide cover?

During the last year, we visited Safed three times. On our first visit, we joined a guided tour. The overview tour showed us the Old City, the Artists’ quarter, and other famous places like Abuhav Synagogue and Ari Ashkenazi Synagogue.

We returned later that year to attend the most popular event in Tzfat, the annual Klezmer Festival.

And our third visit was to see places we did not have time for during our first stay. We headed to the Underground Tunnels and tasted the original Safed Cheese.

This guide will not cover famous burial sites near the city, like Kever Rashbi (Tomb of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai).

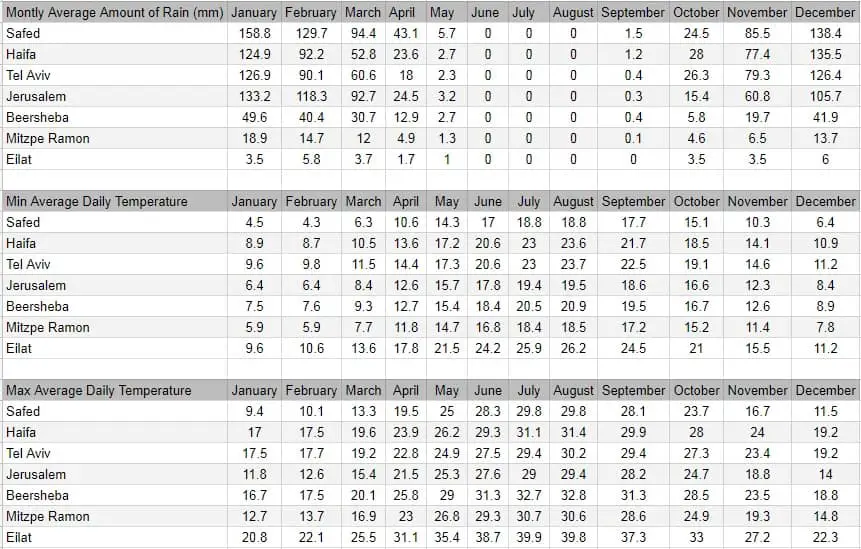

Weather

I want to start this section by presenting data from Events And Festivals By Season.

Safed is the highest city in Israel. Thus, as expected, the temperatures will be lower, and rainfall will be more substantial.

Therefore, from the weather perspective, you can visit Safed all year round. But I would suggest keeping a close eye on the weather during the winter. Rain and slippery sidewalks are half the problem. Sometimes it starts snowing in the city. And though it will be a lovely experience, you might find yourself under a blockade (as all transport halts).

When Not To Visit Safed?

In the previous section, we discussed the weather aspect. But there is also a religious one. Safed is a religious Jewish city. Thus most places will close on Friday afternoon and open only on Sunday. Therefore, do not visit the town on Saturday and Friday afternoon (you can come on Friday morning and tour up to noon or one o’clock).

Tours

As I mentioned, we joined an overview tour on our first visit. When planning the trip, I saw an offer we could not refuse: a free overview tour on the Safed municipality website. I do not see this tour anymore, but they started to offer a wide variety of excursions. Regardless of what you choose, know that taking a tour can be a good option for getting familiar with the town and not getting lost (in the old city) in the process.

While walking in the Old City, I saw this ad for a virtual guide in Tzfat. It is an app called Simtaot. I have not used it, but you might find it helpful.

Saraya

And now, after all the introduction, let’s start with the first visit.

We parked near the Saraya. And here is what a sign tells about this place:

A mid-18th-century structure built by Zahir al-Umar, the Bedouin ruler of Galilee, as a palace for his son Ail, governor of Safed. In 1775, when Zahir al-Umar fell from power, the central Turkish government took over the building. A hundred years later, the building was identified by a British survey as a Turkish khan (inn). At the end of the 19th century, it was restored and transformed into the “Saraya” to house the local Turkish administrator. The square clock tower was added in 1900 in honor of Sultan Abed-el-Hamid II.

In the Mandatory period, the British administration took over the Saraya. During the 1929 Arab riots, all the Jews of Safed were headed into the British’s Saraya courtyard to shelter them from their Arab attackers. Two of the Jews were shot by an Arab policeman assigned to protect them.

During the War of Independence, the Saraya became the central Arab headquarters. Upon the liberation of the city, it was taken over by the Israel Defense Forces. Later is served as a nursing home, and in 1975, after extensive renovation, it became the Isaac and Edith Wolfson community center.

From the Saraya, we followed Aliya Bet street, then turned left on Jerusalem street and followed it (including a left turn) till Tzfat city hall.

Davidka Square

We headed to Davidka Square, near the municipality building, since it was the starting point of our tour.

The Davidka (“Little David”) was a homemade Israeli mortar used in Safed and Jerusalem during the early stages of the 1948 1947–1949 Palestine war. Its bombs were reported to be extremely loud but very inaccurate and otherwise of little value beyond terrifying opponents; they proved particularly useful in scaring away both Arab soldiers and civilians. It is nominally classified as a 3-inch (76.2 mm) mortar, although the bomb was considerably larger.

Source: Wikipedia

Davidka was named after its inventor David Leibowitch, but the reference to David and Goliath is inevitable.

The City Police Station

And near the Davidka, you can find the remains of a British police station.

In the photo above, you can see a part of it. The nearby building of Zefat Academic college was also part of the police station. And if you look closely, then you can see numerous bullet holes in both of these buildings.

A British police building is one of a series of forts erected in critical locations throughout Palestine by Sir CharlesTegart, one of Britain’s top military experts. It was built in the late 1930s on the main street, at the top of the long stairs (“Ma’ a lot Oley HaGardom” of today) that buffered between the Jewish and Arab quarters. It served as a regular police station with mostly Arab and a few Jewish policemen in peace times. The courtyard was surrounded by concrete walls (which were demolished after the War of Independence). There was a tall concrete pillbox at one end. The bullet holes in the main building’s facade and on the pillbox are testimony to the fierce battle that took place here in 1948.

The city police station was handed over to the Arabs when the British evacuated Safed, April 16, 1948, along with several other vital positions in the city. The longest and fiercest battle took place here on May 10, in which the company commander, Yitzhak Hochman, was accidentally killed.

A commemorative plaque is fixed to the pillbox façade. There are two additional plaques in memory of the soldiers Amishalom Milkovsky and Refael Eddrei, local defenders who fell in “Operation Yoav” for the liberation of the Negev.

The main police building was occupied by the IncomeTax Department for many years. Today it is part of the Zefat Academic College.

Source: sign

Today this building serves as a tourist information center. Also, behind it, you can find restrooms.

At this point, we met our guide and headed to the Old City.

It was a pilot tour. Our guide played and sang, and each had headphones to hear him.

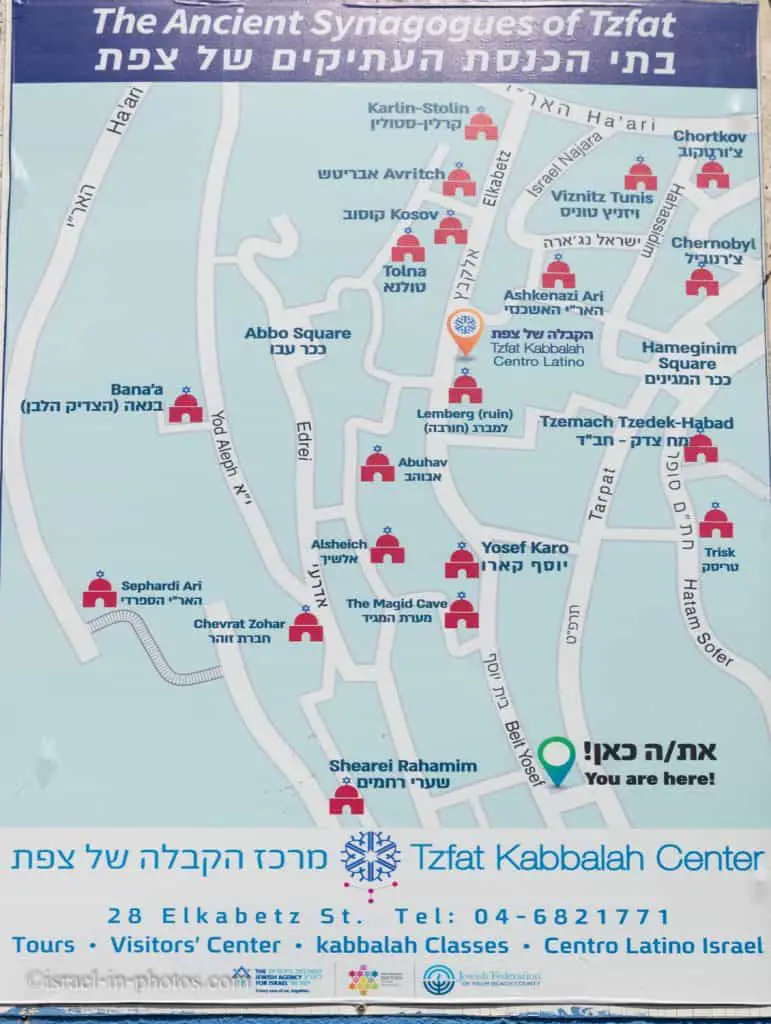

Safed Synagogues

From this point on, during our tour, we mostly visited synagogues. So here is a map of synagogues in Safed.

Many call Safed the city of Kabbalah. Why? Here is one example: shortly, we will visit Ari Ashkenazi Synagogue. And it was named after Isaac Luria, who is considered the father of contemporary Kabbalah.

What is Kabbalah?

Kabbalah (literally “reception, tradition” or “correspondence”) is an esoteric method, discipline, and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist in Judaism is called a Mequbbal. The definition of Kabbalah varies according to the tradition and aims of those following it, from its religious origin as an integral part of Judaism to its later adaptations in Western esotericism (Christian Kabbalah and Hermetic Qabalah). Jewish Kabbalah is a set of esoteric teachings meant to explain the relationship between God, the unchanging, eternal, and mysterious Ein Sof (“The Infinite”), and the mortal and finite universe (God’s creation). It forms the foundation of mystical religious interpretations within Judaism.

Jewish Kabbalists originally developed their own transmission of sacred texts within the realm of Jewish tradition and often used classical Jewish scriptures to explain and demonstrate its mystical teachings. These teachings are held by followers in Judaism to define the Hebrew Bible’s inner meaning and traditional rabbinic literature and their formerly concealed transmitted dimension and explain the significance of Jewish religious observances. One of the fundamental kabbalistic texts, the Zohar, was first published in the 13th century, and the almost universal form adhered to in modern Judaism is Lurianic Kabbalah.

Source: Wikipedia

Safed and Kabbalah

Following the upheavals and dislocations in the Jewish world as a result of anti-Judaism during the Middle Ages, and the national trauma of the expulsion from Spain in 1492, closing the Spanish Jewish flowering, Jews began to search for signs of when the long-awaited Jewish Messiah would come to comfort them in their painful exiles. In the 16th century, the Safed community in Galilee became the center of Jewish mystical, exegetical, legal, and liturgical developments.

The Safed mystics responded to the Spanish expulsion by turning Kabbalistic doctrine and practice towards a messianic focus. Moses Cordovero (The RAMAK 1522–1570) and his school popularized the Zohar’s teachings, which had until then been only a restricted work. Cordovero’s comprehensive works achieved the first (quasi-rationalistic) of Theosophical Kabbalah’s two systemizations, harmonizing the Zohar’s preceding interpretations on its apparent terms. The author of the Shulkhan Arukh (the normative Jewish “Code of Law”), Yosef Karo (1488–1575), was also a scholar of Kabbalah who kept a personal mystical diary. Moshe Alshich wrote a mystical commentary on the Torah. Shlomo Alkabetz wrote Kabbalistic commentaries and poems.

The messianism of the Safed mystics culminated in Kabbalah receiving its most significant transformation in the Jewish world with the explication of its new interpretation from Isaac Luria (The ARI 1534–1572) by his disciples Hayim Vital and Israel Sarug. Both transcribed Luria’s teachings (in variant forms), gaining widespread popularity, Sarug taking Lurianic Kabbalah to Europe, Vital authoring the latterly canonical version. Luria’s teachings came to rival the Zohar’s influence, and Luria stands, alongside Moses de Leon, as the most influential mystic in Jewish history. Lurianic Kabbalah gave Theosophical Kabbalah its second, complete (supra-rational) of two systemizations, reading the Zohar in light of its most esoteric sections (the Idrot), replacing the broken Sephirot attributes of God with rectified Partzufim (Divine Personas), embracing reincarnation, repair, and the urgency of cosmic Jewish messianism dependent on each person’s soul tasks.

Source: Wikipedia

Vizhnitz-Tunisia Synagogue

We followed Shimon Bar Yokhai street until we saw a sign pointing to Vizhnitz-Tunisia Synagogue. And our guide told us the unusual story of this synagogue. You probably guessed by its name. Vizhnitz is the Yiddish name of Vyzhnytsia, a town in Ukraine, and Tunisia is in Africa. So what is the connection?

It started when Rabbi Joshua Pitussi migrated to Israel from Tunisia in 1949. He gathered other Jews from Tunisia and looked for a place to pray. Rabbi Kaplan offered to use the building of Vizhnitz. But one of their conditions was that Vizhnitz should remain in the name. Thus today, we got a synagogue with a multi-continent name.

Messiah’s Alley

We continued along Shimon Bar Yokhai street till we reached Messiah’s Alley. Our guide told us about Grandma Yocheved. She was sitting every day on these stairs and waiting for the Messiah.

A steep alley with stairs, the narrowest of all Safed’s alleys that has become famous in the city thanks to Yocheved Rosenthal, whose house stood at the bottom of the stairs. “Grandma Yocheved,” as she was known to all, used to sit at the entrance to the alley in anticipation of the Messiah’s arrival.

The old lady, who outlived her entire family, believed that the Messiah would pass through Tzfat on his way to Jerusalem and would surely enter the city via her alley. The thin metal pipes that the Jewish Municipality of Sated installed for her as hand-rails can still be seen on either side of the alley.

Source: sign

We descended the alleys in the Old City till we reached Safed Yeshiva.

Safed Yeshiva

Note: I marked all points of interest on the Google Map above to make it easier to follow our path.

Safed Yeshiva is located near Ari Ashkenazi Synagogue in a small alley connected to Israel Najara street.

To the general Israeli public, Safed Yeshiva is known as Yeshiva, which has an agreement with IDF. Yeshiva students have a dedicated course where they learn and serve in the IDF.

Safed Candles

From Safed Yeshiva, we walked along Israel Najara street to Safed Candles. Our guide gave us some free time. While some used it to visit nearby restrooms, we headed to Safed Candles. You can find the complete guide at Safed Candles.

Ari Ashkenazi Synagogue

After visiting Safed Candles, we headed to the nearby Ari Ashkenazi Synagogue (marked as #10 on the map at the beginning of this post). To find additional details about this place, see Ari Ashkenazi Synagogue.

From Ari Ashkenazi Synagogue, we continued to Alkabets street, where you can find the entrance to the underground tunnels.

And in front of the Underground Tunnels, at Alkabets 18 street, you can find the Lahuhe original – Yemenite food bar.

Our guide recommended this place, and we continued to our next point of interest as we passed.

Abuhav Synagogue

Our next stop was the Abuhav Synagogue (marked as #20 on the map at the beginning of this post). To find additional details about this place, see the guide to Abuhav Synagogue.

Blue Color in Safed (Tzfat)

As you visit Safed, you will notice one dominant color. Blue appears everywhere. It decorates synagogues, fences, walls, and other items.

Nobody is sure what is the exact reason. But I will list several of the common explanations that I found. That is not a new tradition, and in the 16th century, the houses were painted blue.

- The Torah commands Jews to put a blue thread in the tallit (prayer shawl). Rabbi Yosef Karo commented that blue suggests the heavens, which induces the thought of God. Thus the color helps direct thoughts and prayers to God.

- Blue serves as a virtue against the evil eye, alienating spirits and demons.

- Tzfat is the gateway to the sky, and the blue color connects the houses and the sky.

- Blue paint repels insects.

- Women used to whitewash the houses themselves. Back then, the colors were not widespread. Moreover, the colors were costly. One woman, tired of the white color, decided to add to the lime (Calcium oxide), the blue laundry substance available in every home. As a result, the house’s walls suddenly became cheerful and happy instead of the dull white paint. And soon others followed.

We reached the end of the guided tour, and to give you a time perspective, I will say that it lasted almost two hours.

When the tour ended, we wandered at Artists’ Quarter for a while and then went to eat.

Lahuhe original – Yemenite food bar

As I mentioned above, Lahuhe original is located at Alkabets 18 Street, and following our guide’s recommendation, we decided to try it.

Lahoh

Let’s start with a fundamental question. What is Lahoh? Lahoh or Luhuh is a porous, pancake-like bread that originated in Yemen.

Lahoh is prepared from a dough of plain flour, self-raising flour, warm water, yeast, and a pinch of salt. The mixture is beaten by hand until soft and creamy. Sorghum is the preferred flour for making Lahoh. A sweet-tasting variety of the dish and another variety made with eggs.

Lahoh is traditionally baked on a metallic circular stove called a Taawa. Lacking that, it can also be baked in an ordinary pan.

Source: Wikipedia

They prepared Lahoh on pans and covered it with several types of cheese, veggies, and spices. Then they fold it, and you are ready to eat.

By the time we finished eating, the Underground Tunnels were already closed. Thus we headed to Safed citadel. But do not worry, we will visit Underground Tunnels on another occasion. You can find the additional details below.

Citadel Park

And our last stop for that day was Citadel Park (marked as #1 on the map).

We took the stairs up, and in the following photo, you can see the City Police Station (where we started our guided tour) to the left and Safed municipality to the right.

You can find informational stands and audio guides in several languages at the entrance to Citadel Park.

Safed Citadel is a central site in the history of the city. The fortress’s beginning is probably in the “Fortress of the Sefaf,” built by Joseph Ben Matityahu (67-66 CE). The extensive excavations carried out at the site since 2001 have not found evidence of this.

At the beginning of the Crusader period (1099-1291), Safed was part of the Galilee Region. In 1102 the Crusaders constructed at their summit their first citadel. In 1179, Salah a-Din tried to conquer the fortress, and only in 1188 was he able to do so. Members of the Ayyubid dynasty ruled the fort for 52 years until the Crusaders returned to Safed in 1240.

The Crusader fortress was rebuilt for two and a half years. It became more extensive, which made it the biggest among the eastern forts. During wartime, according to testimony from that period, there were 2,200 fighters and thousands of residents inside.

In 1266, Baibars, the king of Mamluk-Egypt, succeeded in taking over the fort cunningly, after having failed to conquer by force. He massacred crusaders and their allies and erected a circular tower that was 60 meters high.

In the Ottoman period, which began in 1516, the city of Safed expanded. But the citadel was neglected, and its stones were taken for construction and lime production. In the 18th century, in the days of the Al-Omar Bedouin ruler of Galilee, the fort was partially restored. In 1799, during Napoleon’s journey to Acre, the fort was briefly conquered.

In the 1837 Great earthquake, the citadel was destroyed. It was not restored since.

At the beginning of the British Mandate, many pine trees were planted on Citadel Hill. At the summit, the British established a fortified military post, which overviewed the entire city. In 1948, the fortress was handed over to the Arabs, and it was captured on the night of the liberation of Safed. In 1951, the castle garden was created. The excavations at the site reveal considerable parts of the Crusader, Mamluk, and the Ottoman fortress structures.

Source: translated from a sign on site.

And as we mentioned in the naming section, Safed probably got its name for being on high grounds. And even on a not very clear day, you can see the Sea Of Galilee.

Klezmer Festival

Klezmer Festival has been held annually in Tzfat for more than thirty years. It usually takes place around the Old City. And for three consecutive nights, you can enjoy a variety of free concerts.

Klezmer

Here is a short description from Wikipedia:

Klezmer is a musical tradition of the Ashkenazi Jews of Eastern Europe. Played by professional musicians called klezmorim in ensembles known as Kapelye, the genre originally consisted largely of dance tunes and instrumental display pieces for weddings and other celebrations. In the United States, the genre evolved considerably as Yiddish-speaking Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, who arrived between 1880 and 1924, came into contact with American jazz. During the initial years after the klezmer revival of the 1970s, the American sub-variety was what most people knew as klezmer, although in the 21st-century musicians began paying more attention to the original pre-jazz traditions as revivalists including Josh Horowitz, Yale Strom, and Bob Cohen have spent years doing field research in Eastern/Central Europe. Additionally, later immigrants from the Soviet Union, such as German Goldenshtayn, took their surviving repertoires to the United States and Israel in the 1980s.

At Safed Klezmer Festival

We visited the 32nd Klezmer Festival in August 2019. And as I mentioned above, the festival takes place for three nights. We looked at the list of performers (you can find it on the municipality site) and decided to visit on the third night.

There is heavy traffic in the city on these nights, and many streets are closed to cars. We were directed to a big parking lot at the market and walked to the municipality building.

The relevant streets became pedestrian-only, and there were many food stands.

But I was a little disappointed by the selection of food. I did not see anything beyond the standard. Mostly you could find Bourekas, pizza, and Shawarma.

There are several performance stages across the city. And we headed to the municipality stage. But beyond the artists on the big stages, there are also many street performers.

Klezmer comes from a combination of two Hebrew words (Klei and Zemer). Literary meaning musical instruments.

Also, since the streets are packed with people, reaching each place will take more time.

We choose to see Sanya Kroytor’s concert. We previously went to several of his shows and enjoyed them. Thus it was a natural choice for us.

In the photo above, you can see plastic chairs. But, by the time we arrived, there were none available. And we, like most people, stood during the concert.

This concert ended a little after ten o’clock. But since we were with my older daughter and had a long drive ahead of us, we decided to end the evening.

Overall, this was a lovely experience. And if your favorite performers are about to participate in the Safed Klezmer Festival, then definitely consider visiting.

Artists’ Quarter

On our third visit, we also parked near the Saraya and headed towards Safed municipality.

Ma’alot Oley HaGardom

A little before reaching Safed city hall, you can see a long stair down. It is Ma’alot Oley HaGardom street.

If you look at the map at the beginning of this post, you can see that this street borders the old city and the artists’ quarter. And it is not by chance.

A long, straight stairway constructed by the British towards the end of the 1936-1939 riots as a buffer between the Jewish and Arab quarters. It was controlled by a British gun emplacement above the post office on Jerusalem Street. The large searchlight that lit the stairs at night is still fixed to the roof of the building. In 1948 the stairs were considered the most dangerous defense line of the Jewish quarter, earning them the nickname “Stalingrad Line.” The street is named after seven “Etzel” fighters who were executed by the British in Acre prison (1947) and buried in Safed.

Source: sign on site.

Note: Ma’alot Oley HaGardom is marked as #27 on the map.

Beit Yosef Street

We used the Ma’alot Oley HaGardom stairs to descend from Jerusalem to Beit Yosef street. On Beit Yosef, we turned to the right and headed into the old city. And this is a look in the opposite direction.

We followed Beit Yosef to the Underground Tunnels. In this area, Beit Yosef is a narrow street full of galleries. And here are several photos from that area.

In some galleries, you can see the artists creating.

We purchased several small items and one small drawing, and the prices seemed not too high.

Underground Tunnels

One of the reasons we returned to Safed for the third time this year was the Underground Tunnels. I created a dedicated post. You can find all information at Underground Tunnels.

After the tunnels, we wanted to visit one more place that day. So let’s talk about cheese.

Safed Cheese

Safed cheese is a semi-hard salty cheese originating in the city of Safed. And today, you can still find the original dairies in the city. To find out more, check out Safed cheese.

Note: there are also several wineries in the old city, but since we were with our daughter, and I do not particularly enjoy wine, we decided to taste the cheese.

And that was the end of that trip.

Where To Stay

As long as you are not staying during Jewish holidays (including Saturdays), staying in Safed can be a good choice for people who want to explore the city and Galilee. There are many attractions nearby. Here are several examples: Tzipori National Park, Amud Stream Nature Reserve, Tel Hazor National Park, and Sea Of Galilee with all its points of interest. Moreover, Nazareth and Acre are not too far. And for the complete picture, see the map at the top of this post.

And since it is a city, you can find a range of properties, including hotels, apartments, and B&B.

Booking.comHistory

Here is a shortened historical extract from Wikipedia:

Classical Antiquity

Safed has been identified with Sepph, a fortified town in the Upper Galilee mentioned in the writings of the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus. It is mentioned in the Jerusalem Talmud as one of five elevated spots where fires were lit to announce the New Moon and festivals during the Second Temple period.

Early Muslim period

There is scarce information about the town of Safed prior to the Crusader conquest in 1099.

Crusader period

The city appears in Jewish sources in the late Middle Ages. In the 12th century, Safed was a fortified city in the Crusaders’ Kingdom of Jerusalem, known by the Crusaders as Saphet. King Fulk built a strong castle on a steep hill kept by the Knights Templar from 1168. Benjamin of Tudela, who visited the town in 1170, does not mention any Jews living there. The remains of this castle can now be found under the “citadel” excavations, on a hill above the old city.

Safed was captured by the Ayyubids led by Saladin in 1188 after one year’s siege, following the Battle of Hattin in 1187. Saladin ultimately allowed its residents to relocate to Tyre. Samuel ben Samson, who visited the town in 1210, mentions a Jewish community of at least fifty. In 1227, the Ayyubid emir of Damascus, al-Mu’azzam ‘Isa, had the Safed castle demolished to prevent it from being captured and reused by potential future Crusades. In 1240, Theobald I of Navarre, on his Crusade to the Holy Land, negotiated with the Ayyubids of Damascus and Egypt and finalized a treaty with the former against the latter whereby the Kingdom of Jerusalem regained Jerusalem itself, plus Bethlehem and most of the region of Galilee, including Nazareth and Safed. The Templars, after that, rebuilt the town’s fortress.

Mamluk period

In 1260, the Mamluk sultan Baybars declared the treaty invalid due to the Christians working in concert with the Mongol Empire against the Muslims and launched a series of attacks on castles in the area, including on Safed. In 1266, during a Mamluk military campaign to subdue Crusader strongholds in Palestine, Baybars captured Safed in July, following a failed attempt to capture the Crusaders’ coastal stronghold of Acre. Unlike the coastal Crusader fortresses, demolished upon their capture by the Mamluks, Baybars spared Safed from destruction. Instead, he appointed a governor to be in charge of the fortress.

Baybars likely preserved Safed because he viewed its fortress to be of high strategic value due to its location on a high mountain and its isolation from other Crusader fortresses. Moreover, Baybars determined that a strongly fortified Safed could serve as an ideal headquarters to confront the Crusader threat in a renewed Crusader invasion of the coastal region. In 1268, he had the fortress repaired, expanded, and strengthened. Furthermore, he commissioned numerous building works in the town of Safed, including caravanserais, markets, baths, and converted the town’s church into a mosque. By the end of Baybars’ reign, Safed had become the site of a prospering town, in addition to its fortress. The city also became the administrative center of Mamlakat Safad, a province in Mamluk Syria whose jurisdiction included the Galilee and the lands further south down to Jenin.

Ottoman period

Under the Ottomans, Safed was the capital of the Safad Sanjak, which encompassed much of the Galilee and extended to the Mediterranean coast.

During the early Ottoman period from 1525 to 1526, the Safed population consisted of 633 Muslim families, 40 Muslim bachelors, 26 Muslim religious persons, nine Muslim disabled, 232 Jewish families, and 60 military families. In 1553–54, the population consisted of 1,121 Muslim households, 222 Muslim bachelors, 54 Muslim religious leaders, 716 Jewish households, 56 Jewish bachelors, and nine disabled persons.

Safed rose to fame in the 16th century as a center of Kabbalah, or Jewish mysticism. After the expulsion of all the Jews from Spain in 1492, many prominent rabbis found their way to Safed, among them the Kabbalists Isaac Luria and Moshe Kordovero; Joseph Caro, the author of the Shulchan Aruch and Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz, composer of the Sabbath hymn “Lecha Dodi.” The influx of Sephardi Jews—reaching its peak under Sultans Suleiman the Magnificent and Selim II—made Safed a global center for Jewish learning and a regional center for trade throughout the 15th 16th centuries. A Hebrew printing press was established in Safed in 1577 by Eliezer Ashkenazi and his son, Isaac of Prague. In 1584, there were 32 synagogues registered in the town.

During the transition from Egyptian Mamluk to Ottoman-Turkish rule in 1517, the local Jewish community was subjected to violent assaults, murder, and looting as local sheiks, sidelined by the change in authority, sought to reassert their control after being removed from power by the incoming Turks. The economic decline after 1560 and expulsion decrees depleted the Jewish community in 1583. Local Arabs assaulted those who remained. Two epidemics in 1589 and 1594 further damaged the Jewish presence.

Over the 17th century, Galilee’s Jewish settlements had declined economically and demographically, with Safed being no exception. In around 1625, Quaresmius spoke of the town being inhabited “chiefly by Hebrews, who had their synagogues and schools, and for whose sustenance contributions were made by the Jews in other parts of the world.” In 1628, the city fell to the Druze, and five years later was retaken by the Ottomans. In 1660, in turmoil following the death of Mulhim Ma’an, the Druze destroyed Safed and Tiberias, with only a few of the former Jewish residents returning to Safed by 1662. As nearby Tiberias remained desolate for several decades, Safed gained a critical position among Galilean Jewish communities. In 1665, the Sabbatai Sevi movement arrived in the town.

An outbreak of plague decimated the population in 1742, and the Near East earthquakes of 1759 left the city in ruins, killing 200 town residents. An influx of Russian Jews in 1776 and 1781 and Lithuanian Jews of the Perushim movement in 1809 and 1810 reinvigorated the Jewish community. In 1812, another plague killed 80% of the Jewish population, and in 1819, the remaining Jewish residents were held for ransom by Abdullah Pasha, the Acre-based governor of Sidon. During Egyptian domination (ca. 1831–1841), the city experienced a severe decline, with the Jewish community hit particularly hard. In the 1834 looting of Safed, much of the Jewish quarter was destroyed by rebel Arabs, who plundered the city for many weeks.

In 1837, there were around 4,000 Jews in Safed. The Galilee earthquake of 1837 was particularly catastrophic for the Jewish population, as the Jewish quarter was located on the hillside. About half their number perished, resulting in around 2,000 deaths. Of the 2,158 inhabitants killed, 1507 were Ottoman subjects. The southern Muslim section of the town suffered far less damage. In 1838, the Druze rebels robbed the city for three days, killing many among the Jews. In 1840, Ottoman rule was restored. In 1847, the plague struck Safed again. In the last half of the 19th century, the Jewish population increased by immigration from Persia, Morocco, and Algeria. Moses Montefiore visited Safed seven times and financed the rebuilding of much of the town.

A population list from about 1887 showed that Safad had about 24,615 inhabitants, 13,250 Jews, 5,690 Muslims, and 5,675 Catholic Christians.

British Mandate of Palestine

According to a census conducted in 1922 by the British Mandate authorities, Safed had a population of 8,761 inhabitants, consisting of 5,431 Muslims, 2,986 Jews, 343 Christians, and others. During the British Mandate for Palestine, Safed remained a diverse city, and ethnic tensions between Jews and Arabs rose during the 1920s. With the eruption of the 1929 Palestine riots, Safed and Hebron became major clash points. In the Safed massacre, 20 Jewish residents were killed by local Arabs. Safad was included in the part of Palestine allocated for the proposed Jewish state under the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine.

By 1948, the city was home to around 1,700 Jews, mostly religious and elderly, as well as some 12,000 Arabs. On January 5, 1948, Arabs attacked the Jewish quarter. In February 1948, during the civil war, Muslim Arabs attacked a Jewish bus attempting to reach Safed, and the Jewish quarter of the town came under siege by the Muslims. British forces that were present did not intervene.

On April 16, the same day that British forces evacuated Safed, 200 local Arab militiamen, supported by over 200 Arab Liberation Army soldiers, tried to take over the city’s Jewish quarter. They were repelled by the Jewish garrison, consisting of some 200 Haganah fighters, men and women, boosted by a Palmach platoon.

The Palmach ground attack on the Arab section of Safed took place on May 6 as a part of Operation Yiftah. The first phase of the Palmach plan to capture Safed was to secure a corridor through the mountains by capturing the Arab village of Birya. The Arab Liberation Army had plans to take over the whole city on May 10 and slaughter all as cabled by the Syrian commander al-Hassan Kam al-Maz. In the meantime, they placed artillery pieces on a hill adjacent to the Jewish quarter and started its shelling. The Third Battalion failed to take the main objective, the “citadel,” but “terrified” the Arab population sufficiently to prompt further flight, as well as urgent appeals for outside help and an effort to obtain a truce.

The secretary-general of the Arab League Abdul Rahman Hassan Azzam stated that Plan Dalet’s goal was to drive out the inhabitants of Arab villages along the Syrian and Lebanese frontiers, particularly places on the roads by which Arab regular forces could enter the country. He noted that Acre and Safed were in particular danger. However, the appeals for help were ignored, and the British, now less than a week away from the end of the British Mandate of Palestine, also did not intervene against the second – and final – Haganah attack, which began on the evening of May 9, with a mortar barrage on key sites in Safed.

Following the barrage, Palmach infantry, in bitter fighting, took the citadel, Beit Shalva, and the police fort, Safed’s three dominant buildings. Through May 10, Haganah mortars continued to pound the Arab neighborhoods, causing fires in the marked area and fuel dumps, which exploded. “The Palmah ‘intentionally left open the exit routes for the population to “facilitate” their exodus…’ “According to Gilbert, “The Arabs of Safed began to leave, including the commander of the Arab forces, Adib Shishakli (later Prime Minister of Syria).

With the police fort on Mount Canaan isolated, its defenders withdrew without fighting. The fall of Safed was a blow to Arab morale throughout the region… With the invasion of Palestine by regular Arab armies believed to be imminent – once the British had finally left in eleven or twelve days – many Arabs felt that prudence dictated their departure until the Jews had been defeated and they could return to their homes.

Some 12,000 Arabs, with some estimates reaching 15,000, fled Safed and were a “heavy burden on the Arab war effort.” Among them was the family of Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas. The city was fully under the control of Jewish paramilitary forces by May 11, 1948.

State of Israel

In 1974, 102 Israeli Jewish schoolchildren from Safed on a school trip were taken hostage by a Palestinian militant group Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP), while sleeping in a school in Maalot. In what became known as the Ma’alot massacre, 22 of these school children were among those killed by the hostage-takers after the school had been raided by a special forces unit of the Israel Defense Forces.

Over the 1990s and early 2000s, the town accepted thousands of Russian Jewish immigrants and Ethiopian Beta Israel.

In July 2006, “Katyusha” rockets fired by Hezbollah from Southern Lebanon hit Safed, killing one man and injuring others. Many residents fled the town. On July 22, four people were injured in a rocket attack.

The town has retained its unique status as a Jewish studies center, incorporating numerous facilities. It is currently a predominantly Jewish town, with mixed religious and secular communities and with a small number of Russian Christians and Maronites.

Common Questions

There is no agreement about the origin of the name Safed. But the name Safed resembles the Hebrew word for observing. Therefore, some say that Safed received its name since you can see both the Middeternian Sea and the Sea Of Galilee.

Safed is one of the Four Holy Cities. Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and Tiberias are the four main Jewish centers starting from the sixteenth century. Safed became known as a center of Kabbalistic knowledge.

There are many explanations for the blue color in Safed. For example. Blue serves as a virtue against the evil eye. See other reasons in the Blue Color in the Safed section.

Summary

It took us three visits to see the top sights in Safed (Tzfat), and there are other things to do. Thus, I would recommend spending at least several hours in this city.

Have you ever been to Safed (Tzfat)? What is your favorite place in the city?

That’s all for today, and I’ll see you in future travels!

Stay Tuned!

Additional Resources

Here are several resources that I created to help travelers:- Trip Planner with Attractions and Itineraries is the page that will help you create your perfect travel route.

- What is the Best Time to visit Israel? To answer this question, we will consider the weather, prices, holidays, festivals, and more.

- Information and Tips for Tourists to Israel will answer the most common questions tourists have about Israel (including safety, passports, weather, currency, tipping, electricity, and much more).

- Israel National Parks and Nature Reserves include a complete list, top ten, map, tickets (Israel Pass, Matmon, combo), and campsites.

- If you are looking for things to do, here are the pages for Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Haifa, Sea Of Galilee, Akko (Acre), Eilat, Nazareth, Safed (Tzfat), and Makhtesh Ramon.

hi your website was really informative. Thanks! is there an eruv in tzfat? We have bookings in Rosentalis Hotel for a Shabbat and we have small infant and would love to be able to walk with stroller to old city.

Thanks a lot!

Unfortunately, I do not know. I never stayed in Tzfat for Saturday and did not notice. I asked at the Tzfat municipality’s Facebook page, but they have not replied yet. If they will, I will let you know.

The answer to the question of an eruv is YES! The best place to inquire about its borders would be the office of the rabbinate. Some areas are excluded, of course and I’m only aware of the borders relevant to me, since I live here now. However, the Old City and the Artist’s quarters are inside, as is The Metzuda and possibly parts of the Darom. Call The Rosentalis and ask them also, about the location of the borders. Once you know where to look, the wires and posts are pretty obvious – but other fences and borders are probably included in defining the area.

Thank you for the info, Elisheva.